On June 14, 1969, I won a prize for an essay called “What the Flag Means to Me.” Years in the Boy Scouts informed me of the symbolism in the American flag and taught me flag etiquette. I knew red stood for the blood of American patriots, white stood for the purity of American ideals, while blue stood for the glory of her achievements. I knew you should not fly the flag in the rain or at night, as well as how to fold it smartly into a triangle. I saluted it daily in school and believed that it must never touch the ground or be held in a parade at a lower level than another flag. I had seen enough movies to know that the Stars and Stripes coming over the horizon meant rescue from harm and the restoration of justice. I was proud to wear an American flag patch on the shoulder of my scout uniform.

I was confused by newspaper images of Old Glory being flown upside down (a sign of distress) outside the crown of the Statue of Liberty by Vietnam Veterans Against the War. I was no fan of Abbie Hoffman’s American flag shirt or Peter Fonda’s American flag helmet in Easy Rider. I saw these things as disrespectful.

Then, in 1975, I read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and learned how, in 1864, six hundred Cheyenne, two thirds of them women and children, were massacred, after they sought protection under an American and white flag. When American troops questioned orders to kill even the infants, the commanding officer, Colonel John Chivington, said, “Nits make lice.â€

Continue reading “Flag Day”

On Wednesday, April 14, 2010, Ken Hannaford-Ricardi, Julia Skjerli, and Scott Schaeffer-Duffy of the Saints Francis & Therese Catholic Worker in Worcester, Massachusetts went to the Boston Common where a Tea Party rally addressed by Sarah Palin was held. At the edge of a crowd of about 4,000 Tea Party supporters, the Catholic Workers held signs and distributed almost 500 leaflets. Ken held a sign which read, “A Tea Party the US Needs Now.†It depicted colonists throwing boxes labeled “WAR†into Boston Harbor. Julia held a sign which read, “Cut Government Spending, End the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan Now.†Scott wore a tri-corner hat and colonial garb. He rang a bell and quoted James Madison and Patrick Henry on the evils of a standing army.

On Wednesday, April 14, 2010, Ken Hannaford-Ricardi, Julia Skjerli, and Scott Schaeffer-Duffy of the Saints Francis & Therese Catholic Worker in Worcester, Massachusetts went to the Boston Common where a Tea Party rally addressed by Sarah Palin was held. At the edge of a crowd of about 4,000 Tea Party supporters, the Catholic Workers held signs and distributed almost 500 leaflets. Ken held a sign which read, “A Tea Party the US Needs Now.†It depicted colonists throwing boxes labeled “WAR†into Boston Harbor. Julia held a sign which read, “Cut Government Spending, End the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan Now.†Scott wore a tri-corner hat and colonial garb. He rang a bell and quoted James Madison and Patrick Henry on the evils of a standing army. Ebenezer Scrooge was a businessman whose single employee, Bob Cratchit, a married father of four, worked for starvation wages. In the opening pages of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, we learn that Scrooge believes he is overtaxed by the government and “cannot afford to make others merry.” He doesn’t see himself as a miser, but as a victim of a bad economy. When Cratchit makes even the most modest suggestion of better working conditions (an extra lump of coal on the fire, a single day off a year), Scrooge threatens him with unemployment.

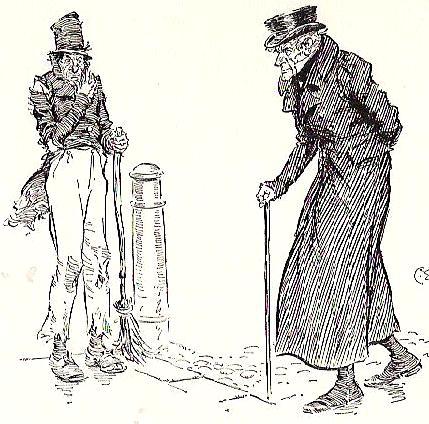

Ebenezer Scrooge was a businessman whose single employee, Bob Cratchit, a married father of four, worked for starvation wages. In the opening pages of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, we learn that Scrooge believes he is overtaxed by the government and “cannot afford to make others merry.” He doesn’t see himself as a miser, but as a victim of a bad economy. When Cratchit makes even the most modest suggestion of better working conditions (an extra lump of coal on the fire, a single day off a year), Scrooge threatens him with unemployment.